During Tessa's first day on the FR2 schedule, she became extremely frustrated with the bar-pressing task and attempted to escape from the box. She investigated each side of the cage for any way to escape. For instance, she tried pressing her way through the top of the front window of the Operant box. When she returned to the bar, she realized that there was a second light above the magazine which she could grasp with her front paws. She began to rear, then suddenly she jumped from the floor of the Operant box and grabbed onto the light with her front paws. Tessa pulled herself to the very top of the box, and with all of her might she kicked her hindlegs to the light fixture and grasped onto it with her feet. Being the most agile of her sisters, she was quick to kick herself from the light fixture to the middle of the top of the Operant box. She grasped onto the top of the box and attemped to escape from the top of the box (as shown below).

Even though she was unable to pull herself through this small opening, it did not deter her from trying to escape

every day during training. Many sessions would end with Tessa receiving a reinforcement, using her ninja-rat skills to attempt to escape, failing and falling from the top of the Operant box, then returning for reinforcement and repeating the cycle. I thought this behavior was affecting the efficiency of her training, so I attempted to correct it for FR15 and FR20 schedules.

Goal:

To reduce the amount of time Tessa spent attempting to escape the Operant box through the top of the box by blocking the opening in the top of the box.

Procedure:

In order to completely block Tessa from escaping through the top of the box, I attained a large clipboard and placed it over the top of the box. This blocked the large opening in the top of box as well as smaller openings she could grasp onto towards the front of the box.

Results:

Tessa spent less time attempting to escape through the top of the Operant box, but she continued to explore the box at a comparable rate. She spent more time trying to push her face through the bottom of the box.

Discussion:

Tessa's variable behavior was very useful in shaping the bar-pressing behavior because it gave me a lot of possible behaviors to attempt to train towards bar-pressing. However, her excitability did pose a problem during training sessions because she would spend a great deal of time exploring the box when she could be training. The clipboard was successful in preventing her from escaping from the top of the box, but it did not stop her from climbing to the top of the box. I think it would have been more useful to train an incompatible behavior (such as rewarding her for staying on the bottom of the cage), but the time restraints on this project made the restriction of escape a more viable option.

I believe this adjustment did make a difference in the final days of training, and she spent more time training during the FR15 and FR20 schedules than exploring the box. However, this change could be attributed to the fact that she had to work harder to receive reinforcement than in previous schedules. Likewise, she was less likely to become satiated because reinforcements took longer and more work to receive. Nevertheless, preventing her from receiving the satisfaction of putting her head outside of the box prevented her from attempting to escape from the top of the box during the final days of training and extinction.

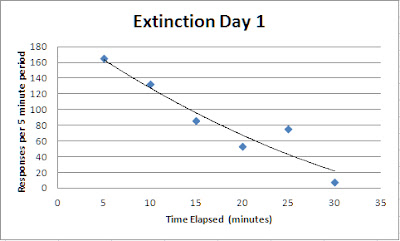

On a more general note, I believe my training could have been improved by extending the amount of time spent working in the Operant box. Because shaping lasted for an average of 20 minutes, I believe Tessa expected future training sessions to only last around 20 minutes. She performed a majority of her bar-presses during the first ten minutes of training sessions, and typically she was satiated by the time 15 minutes had been elapsed. However, Tessa did respond during the final minutes of training sessions after 20 or 25 minutes of training. Therefore, I believe Tessa made adequate progress in her training regardless of her tendency to respond at dramatically lower rates towards the end of each training session. She learned the amount of bar-presses required to receive reinforcement, and I never ended a training session until she was consistently responding on the desired schedule.